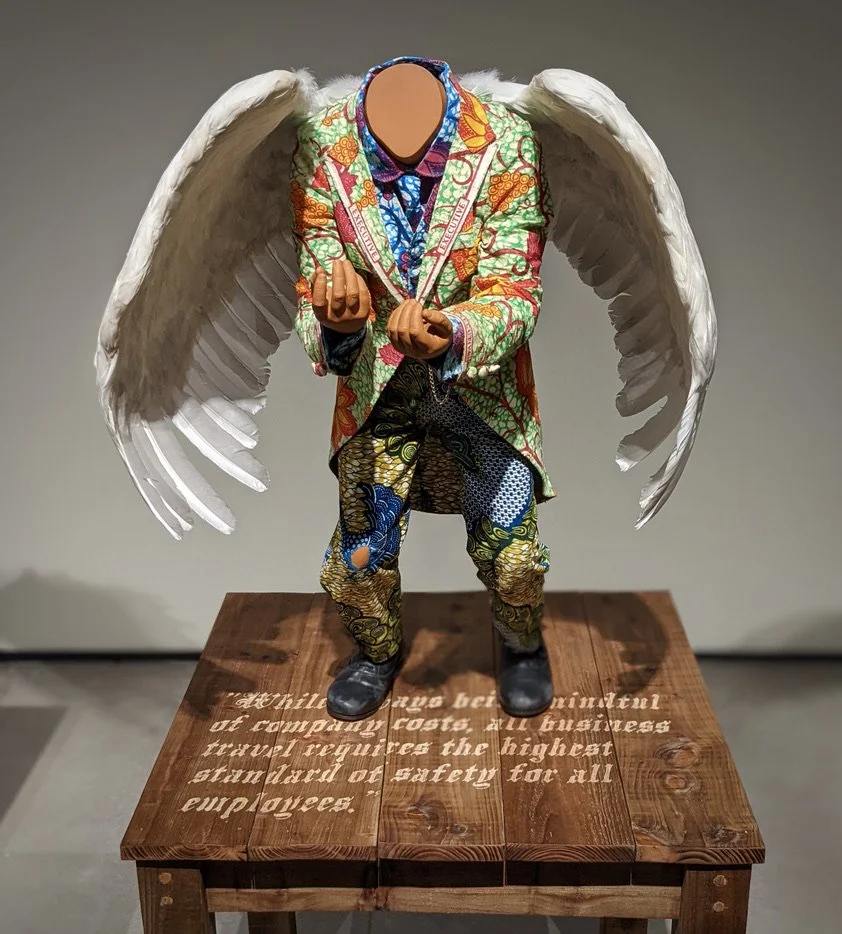

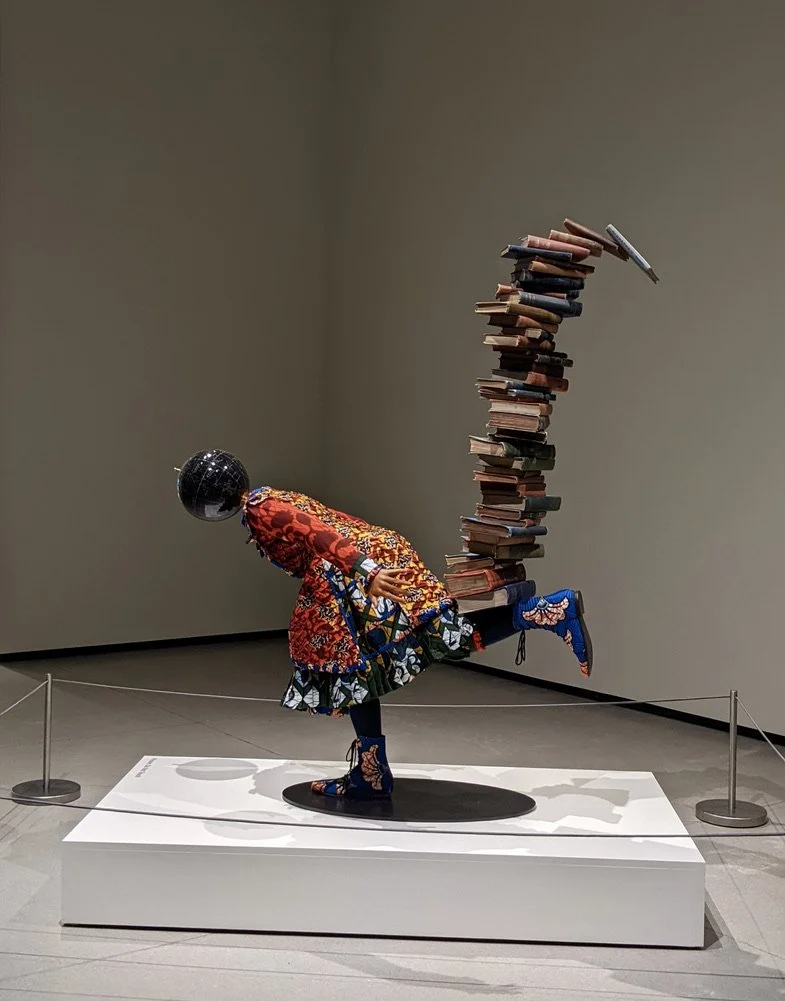

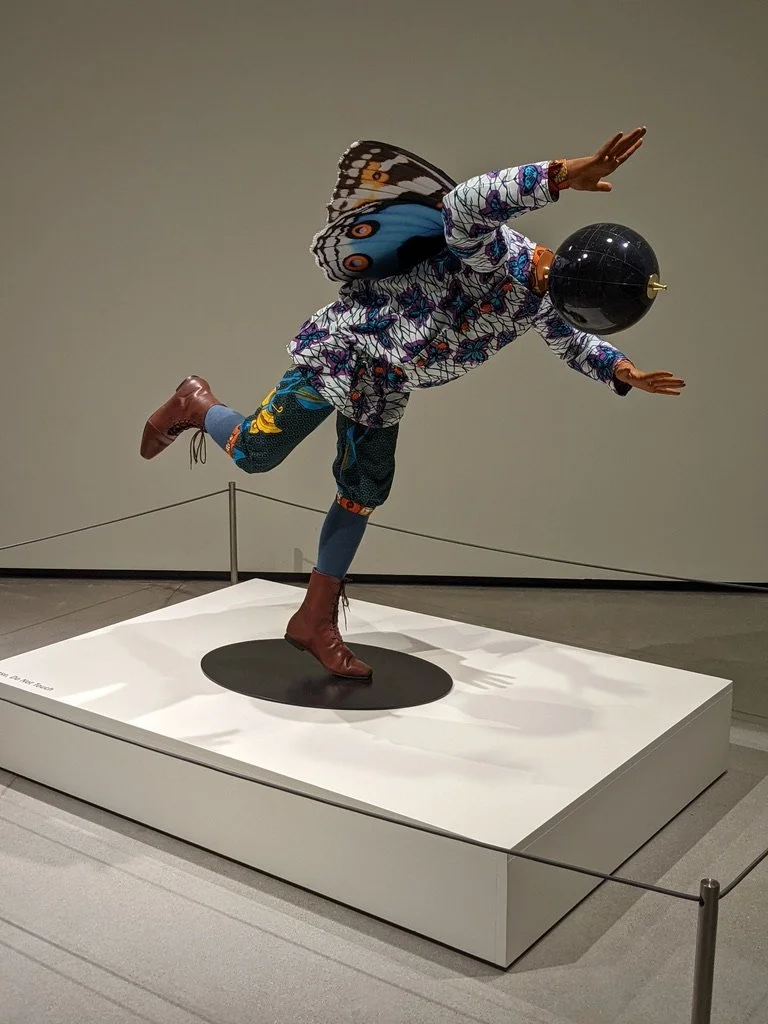

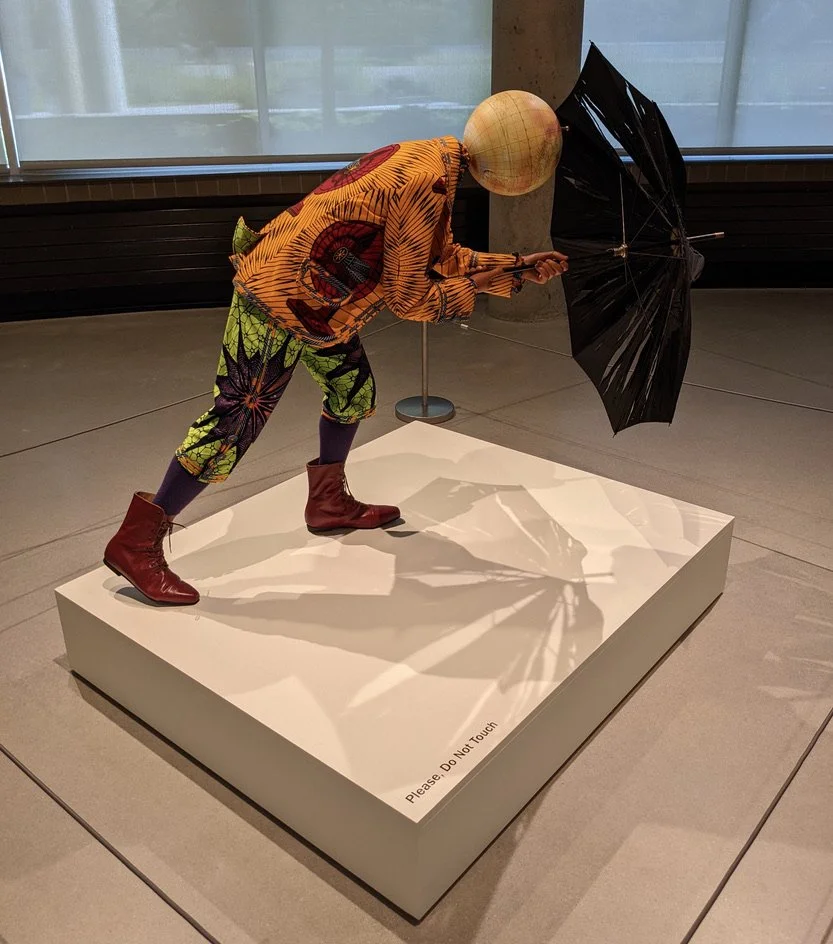

As much as we enjoyed our stroll through the grounds of the Meijer Gardens and Sculpture Park this summer, the highlight of our visit actually occurred before we even left the welcome center. It was there that we stumbled across several rooms of headless, terracotta-toned mannequins, each life-sized and bedecked in layers of fantastically contrasting color and pattern. In some cases, the truncated necks were topped by globes; in another, a serene, upright Ife bust replaced the anxious expression and downward tilted head of Donatello’s sculpture of the Prophet Habakkuk. In every instance, the figures wore European style clothing dating from antiquity to the 19th century, made from the Dutch wax fabrics widely used in Africa.

These creations, along with photographs, prints, and painted masks, were part of the retrospective solo show Yinka Shonibare CBE: Planets in My Head. Shonibare, whose full professional name and titles are Yinka Shonibare CBE RA (Commander of the Order of the British Empire and Royal Academician), is “a self-proclaimed ‘postcolonial hybrid’ of British-Nigerian heritage,” who was born in England to Nigerian parents, studied art in London, and grew up between Lagos and the UK. An even more complex hybridity has formed the basis of his sculpture, photography, and paintings over the last three decades, work which interrogates our notions and assumptions about cultural and national divisions while celebrating a more nuanced understanding of our global history and present.

He became best known for his method of citing and recreating parts of famous works of Western art as installations while redressing the figures in the brightly printed wax cotton fabric associated with much of Africa. Originating in the 19th century, this fabric is not only a multicultural product but also a transcontinental one, owing its creation to the waxed batiks of Indonesia, traders and producers from the Netherlands (particularly Vlisco), and the tastes of elite buyers in central and western Africa.

Yinka Shonibare, The Swing (After Fragonard), 2001. Collection of Tate Modern (not on view in the Meijer exhibition). Photo courtesy Art21.

I first saw Shonibare’s work twenty years ago at the Studio Museum in Harlem during a period when, as a college student, I was writing about and grappling with issues related to transculturalism, the African diaspora, and American (and, to a lesser extent, British) art institutions. At the time, I had been particularly struck by The Swing (After Fragonard) [above], which plucked the iconic central figure from Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s frothy 18th century painting The Swing (Les hazards heureux de l’escarpolette) [below], swapped out her clothes, popped off her head, and inserted her into real space to create a surprising and, frankly, delightful mise-en-scène. It was impossible not to be drawn into the installation’s visual ironies of a figure that was at once playful and beheaded, freewheeling and frozen, lifelike and untouchable, and, of course, stereotypically European and stereotypically African.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Les hasards heureux de l'escarpolette (The Swing), c. 1767–68. Wallace Collection, P430. (Not on view in the Meijer exhibition.)

Reencountering his work now was a bit like visiting a promising and much missed friend after a long separation. Mostly, it was warm and exciting and wonderful to see his continued success while reacquainting myself with his oeuvre. Yet, it is hard to recapture how timely and impactful that initial encounter was back in 2002. Once the glow of reacquaintance faded, I had to admit I would have liked to have seen more experimentation and growth in his recent creations, without which the show as a whole could not help but feel a bit repetitive and stale. Taken individually, though, the sculpture in the Meijer galleries still rewarded long and careful looking.

As has always been the case, Shonibare’s sculptural interventions at first read as celebratory, crowd-pleasing reminders of the interconnectedness of the world, particularly in the colonial and post-colonial periods, playfully undermining any ideas of cultural essentialism. The colorful re-contextualizations and reinvigorations of famous images, objects, people, or texts easily sweep viewers away with the pure pleasure of their spectacle. However, his more layered works also include reminders that the relationships between colonizing and colonized nations are far from easy. In Girl Ballerina (pictured at top and bottom), Shonibare has recreated Edgar Degas’s Little Dancer Aged Fourteen (1878–81), redressing her in wax-printed cloth, enlarging her to life-size, and removing her head. More subtly, the girl’s hands are no longer clasped behind her to stretch her muscles. Instead, they hide an antique gun, a change only visible once the visitor has walked around the sculpture or approached it from behind. Who the menacing gun is for and who the dancer herself is, however, are left effectively ambiguous.

Yinka Shonibare CBE: Planets in My Head was open March 1–October 23 2022 at the Frederik Meijer Gardens and Sculpture Park in Grand Rapids, MI. Hover over images for more information on each work.