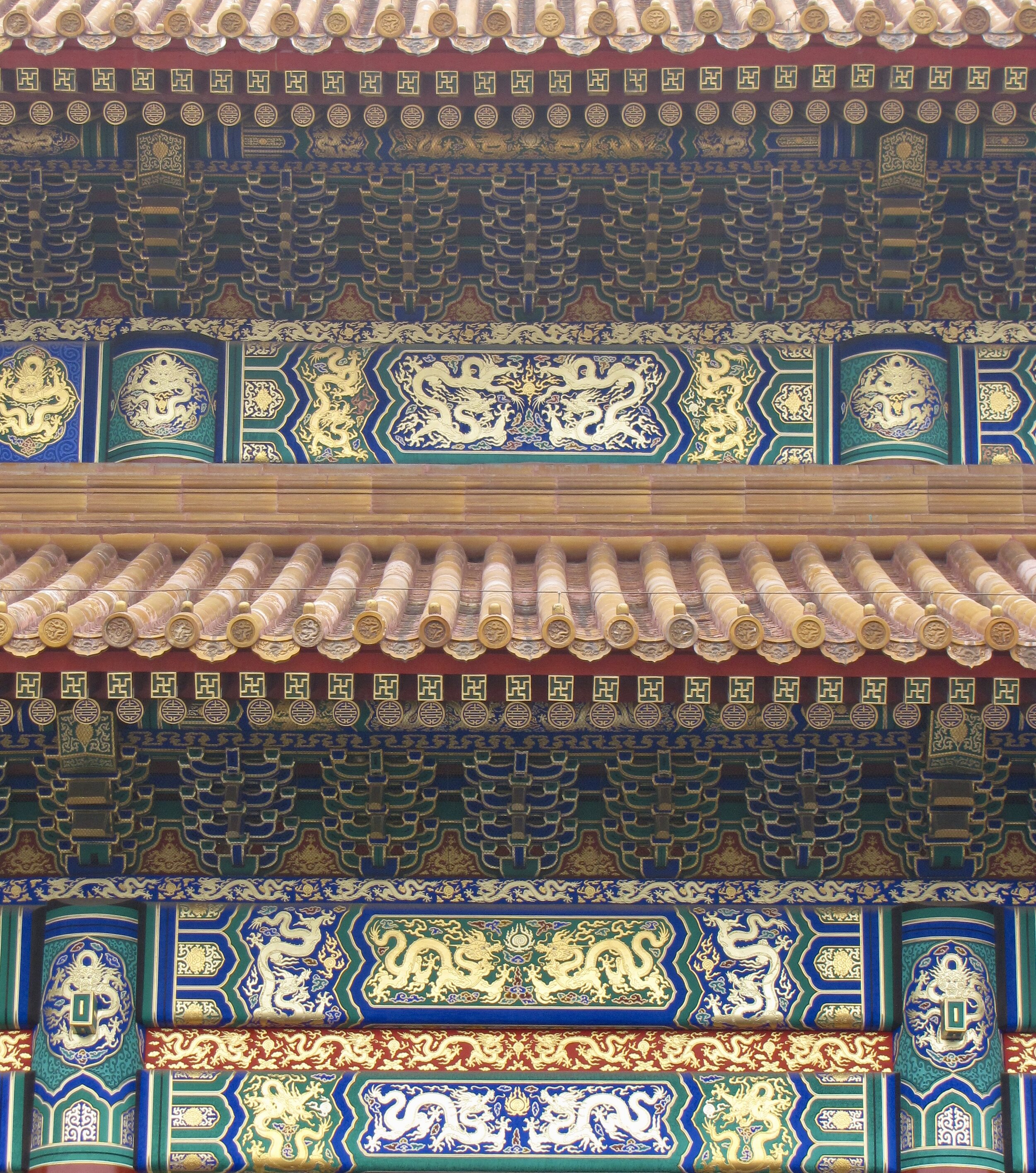

Detail of a dragon on a panel in the Forbidden City, Beijing, China. In Imperial China, only the emperor’s family could possess depictions of dragons. Five-fingered dragons, like the one seen here, were specifically for the emperor. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.

Four-fingered dragon on the Nine Dragon Screen of Datong, China. While five-fingered dragons were only for the emperor, four-fingered dragons were for other members of the imperial family. In this case, the dragon screen was built in the late 14th century at the palace of Zhu Gui, thirteenth son of the Ming dynasty’s first emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.

The emperor’s five-fingered dragons on a wooden panel at Da Ci’en Temple, Xi’an, China. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.

Four-fingered dragon on the Nine Dragon Screen of Datong, China. Screen-walls were constructed within palace gates to protect homes from negative energy and unwelcome spirits. Dragons—as symbols of luck and power—were particularly potent protectors, always appearing in odd numbers, from one to nine. Built in the 14th century, Datong’s Nine Dragon Screen is the largest and oldest extant glazed screen, outlasting even the palace it was built to protect. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.

The emperor’s five-fingered dragons bracketed by phoenixes, symbols of the empress, at the Summer Palace, Beijing, China. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.

Detail of one of the four-fingered dragons on the Nine Dragon Screen, Datong, China. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.

Dragons in the Forbidden City, Beijing, China. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.

Four-fingered dragon on the Nine Dragon Screen in Datong, China. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.

Dragons on a decorative panel in the Forbidden City, Beijing, China. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.

Detail of the Nine Dragon Screen in Datong, China. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.

Da Ci’en Temple, Xi’an, China. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.