In the Sudanese Valley, just south of ancient Egypt, another major civilization once bloomed along the Nile. Now known collectively as Nubia, the cultures of this region sat at the crossroads of Central and Eastern Africa, the Mediterranean, and Western Asia and encompassed many different kingdoms over a 6000 year history. One of the earliest was the Kerma culture (2500–1500 BCE), which began in north-central Sudan and stretched upward, eventually extending to the Egyptian border and engulfing the Sudanese kingdom of Sai.

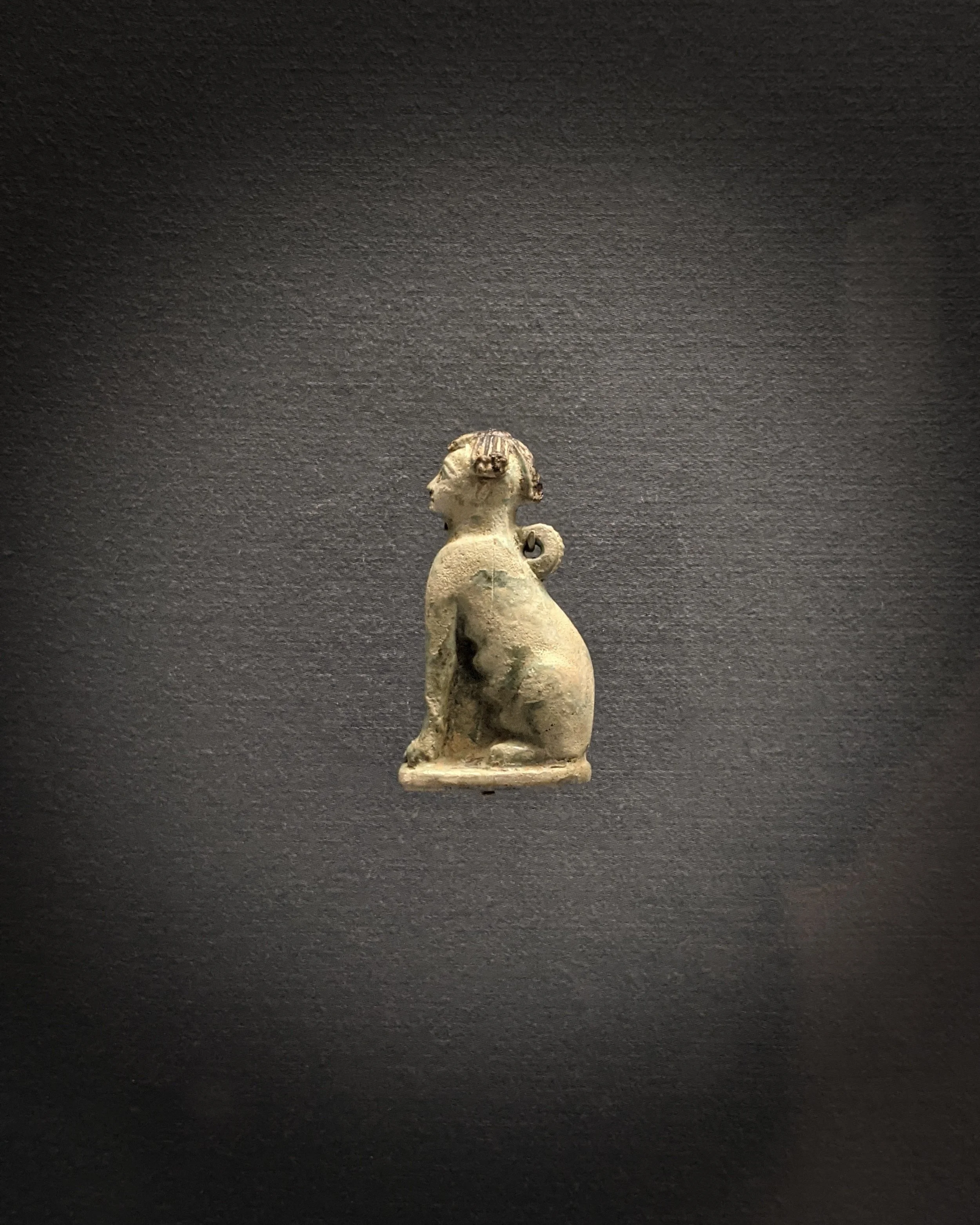

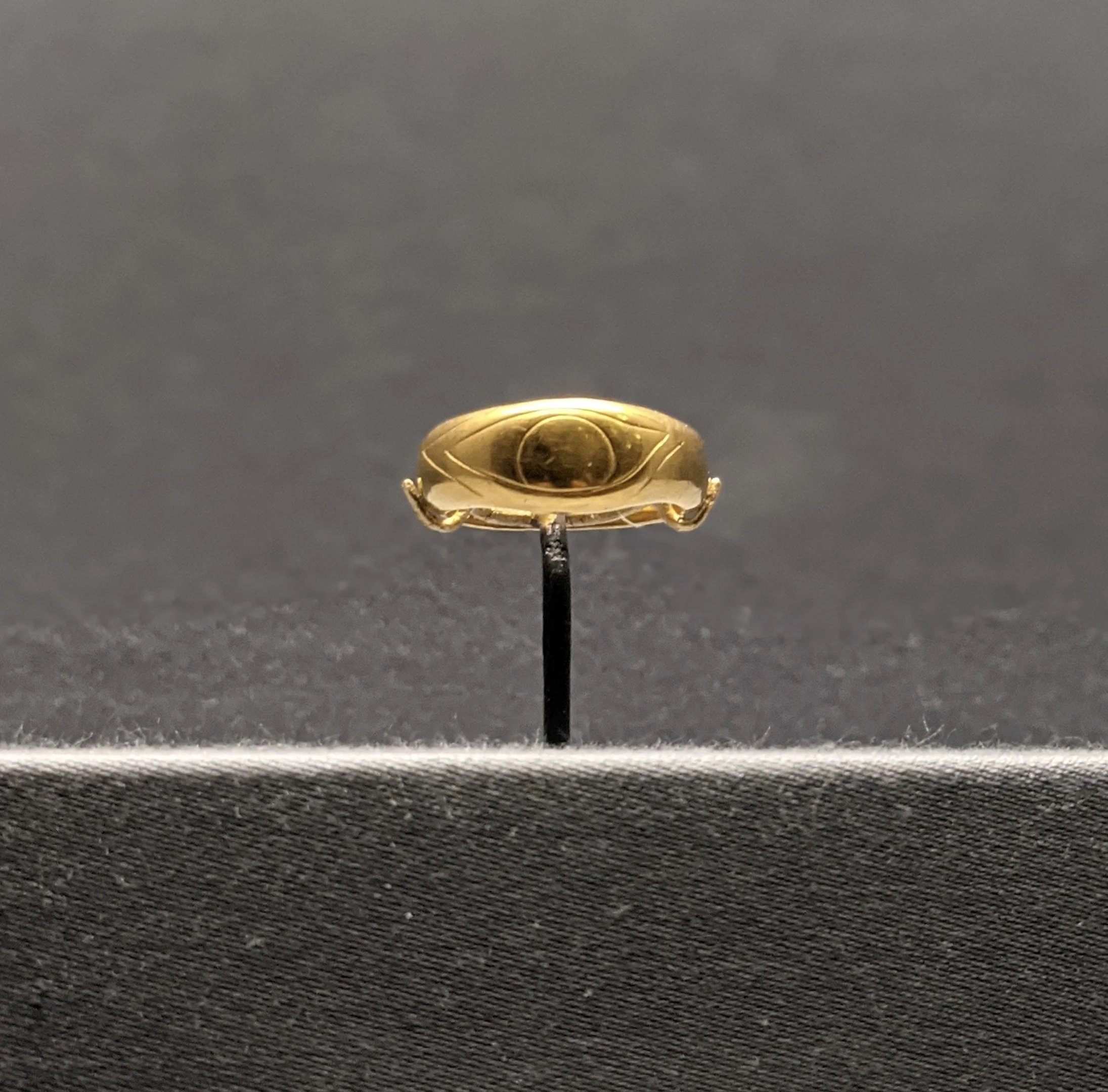

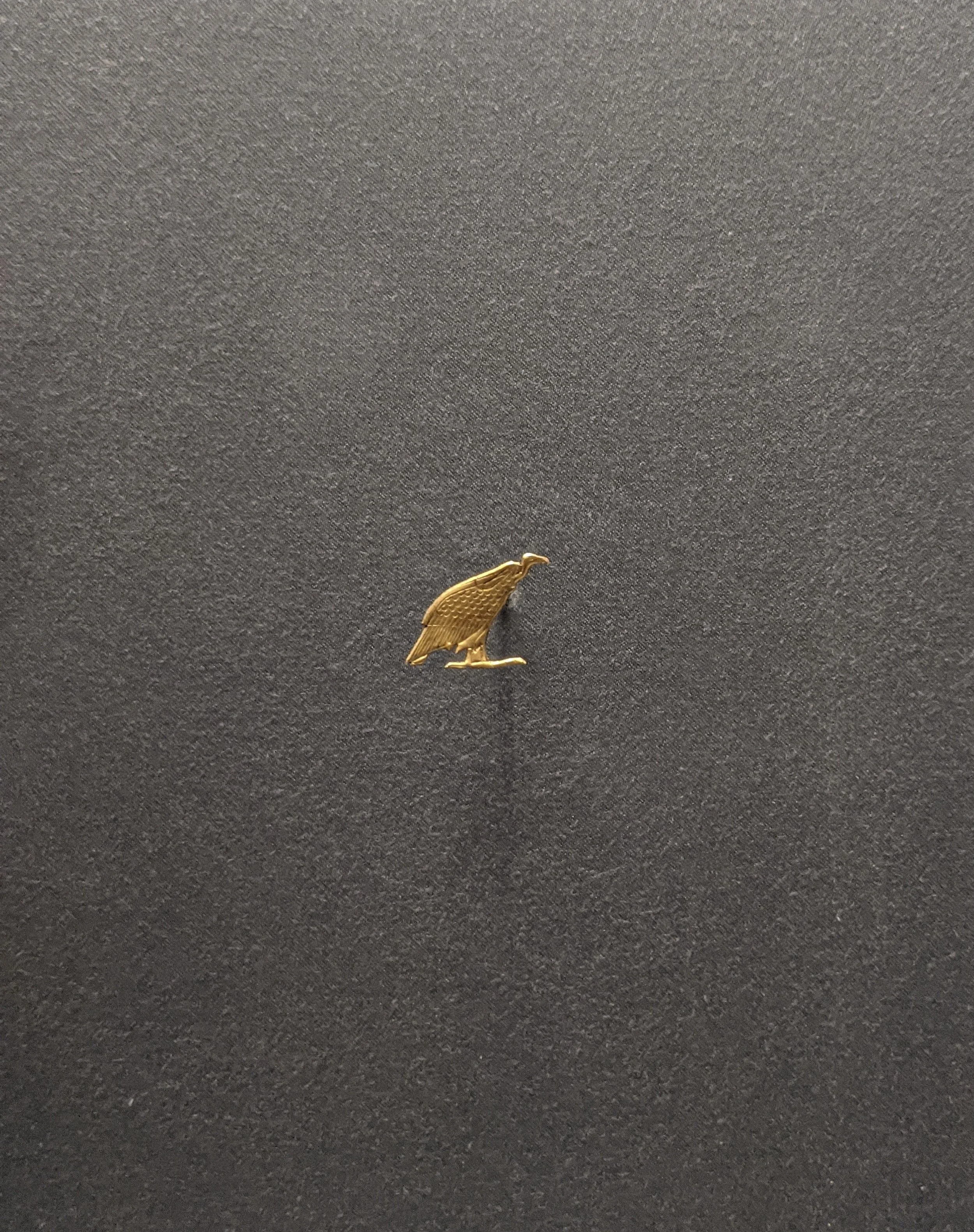

Kerma was subsequently sacked and Nubia (whose peoples were first referred to as the Kush by the Egyptian Middle Kingdom ruler Mentuhotep) annexed by Egypt. The relationship between Egypt and the Kush was never seamless, however, and as Egypt’s power waned, eventually resulting in the disintegration of the New Kingdom, the independent Kingdom of Kush rose. This new Nubian society centered first in the Sudanese city of Napata and then Meroe, also referred to as the Napatan (900–270 BCE) and Meroitic (270 BCE–350 CE) cultures. The Kushite kingdoms of these periods utilized and adapted certain Egyptian iconography, practices, and styles in their grave goods, which were both inherited culturally from the time of Egypt’s rule and brought in as trade goods or war spoils.

Like too many Americans, I knew (and, honestly, still know) very little about Nubia. Of course, it is that very ignorance the exhibition Nubia: Treasures of Ancient Africa sought to combat. Organized by Denise Doxey, curator of ancient Egyptian, Nubian, and Near Eastern art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), the exhibit travelled to the Saint Louis Art Museum, where I had the pleasure of seeing it in the summer of 2021. The MFA’s collection of Nubian art is the largest outside of Khartoum, Sudan and, in the words of the museum’s collection page, “owes its existence to the pioneering efforts of George A. Reisner, who was granted permission by the Sudanese government to excavate 11 sites in northern Sudan from 1913 to 1932.” As part of this agreement, the uncovered objects were then split between Sudan, as the host country, and the excavators. It’s Reisner’s portion that now makes up the MFA’s collection.

The exhibition in St. Louis focused on burial goods made during the 2000 years that stretched between the Middle Kingdom and Meroitic periods. With one or two exceptions, the objects pictured here were excavated at Kerma, Meroe, Gebel Barkal (also of the Meroitic period), or the sites of the Napatan region, including Nuri and el-Kurru. All appear to have been either made locally or imported from Egypt or the Roman Empire.

The information I’ve included in this post, including that in the picture captions, comes from the exhibition texts, with supplements from the MFA, exhibition, and UNESCO websites, as well as Wikipedia.