In 1869, the brothers Louis and Gustav Castan opened their “Panopticon,” a kind of natural history museum-cum-funhouse, in the center of Berlin. Throughout the Panopticon’s run, the heart of its collection lay in its extensive collection of human waxworks, which included everything from anatomical models to Madam Tussaud’s-style celebrity likenesses. Unlike the more instructional models produced in Florence and Bologna during the 18th century, the figures that filled the panoptica of this period were primarily meant to entertain the general public, designed to titillate, horrify, fascinate, and even stir national pride.

Castan’s Panopticon was popular in its first decades, expanding to larger buildings twice by 1888. However, its waxworks seemed to fall out of favor in the early 20th century. Their charms may have begun to pale next to more modern entertainments, like cinema, or the institution may simply have fallen victim to Germany’s increasing economic strife. Whatever the case, Castan’s Panopticon closed in 1922, and its collection remained in storage for nearly a century.

Then, in 2016, oddities dealer Ryan Matthew Cohn found them a home on the other side of the Atlantic through a new buyer: Tim League, CEO of Alamo Drafthouse movie theaters. Now, under Cohn’s curatorship, the collection lives anew, on public display in one of League’s New York properties.

And that, in a nutshell, is the story of how a collection of 19th century German waxworks wound up lining the walls of a bar in a Brooklyn mall.

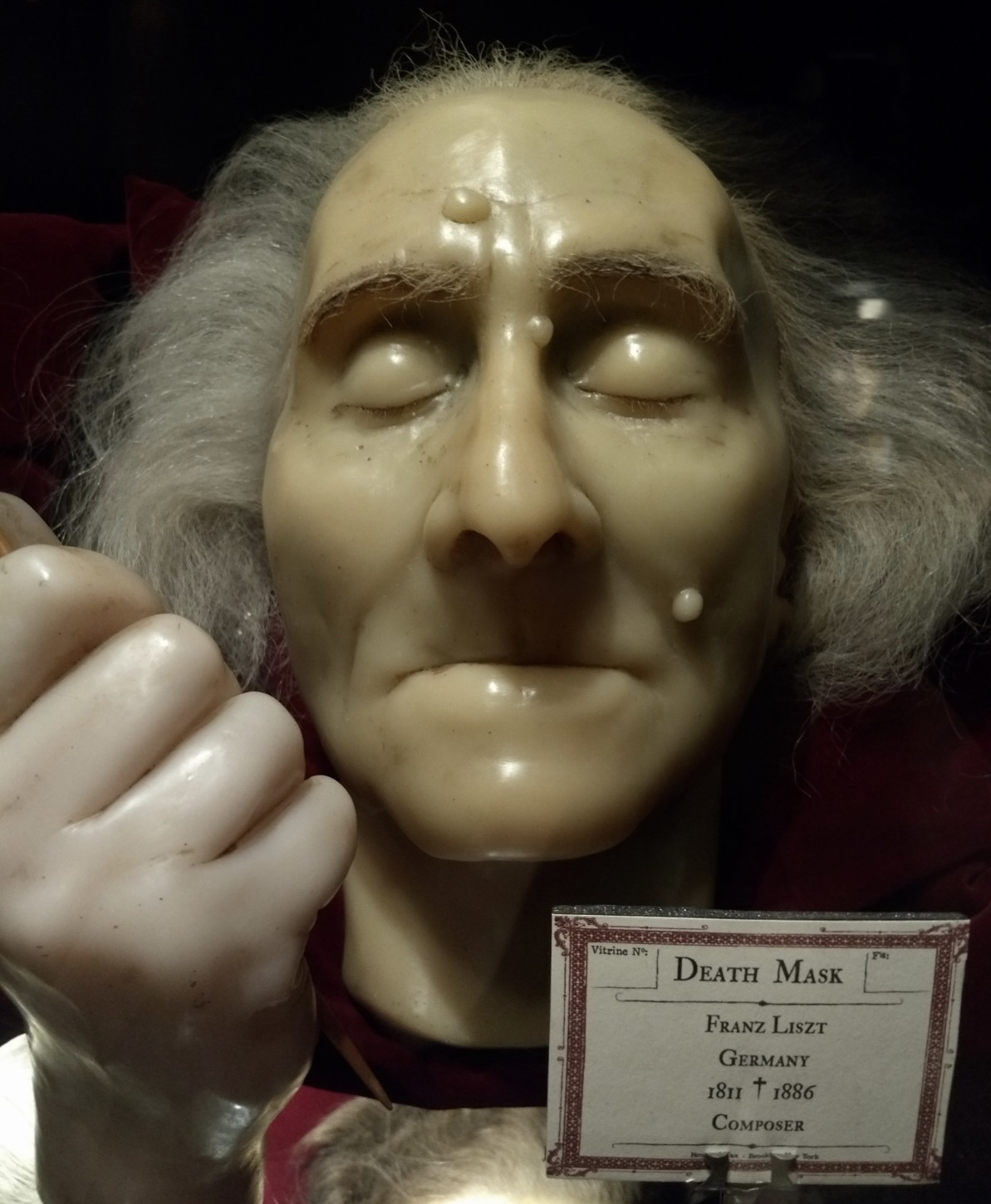

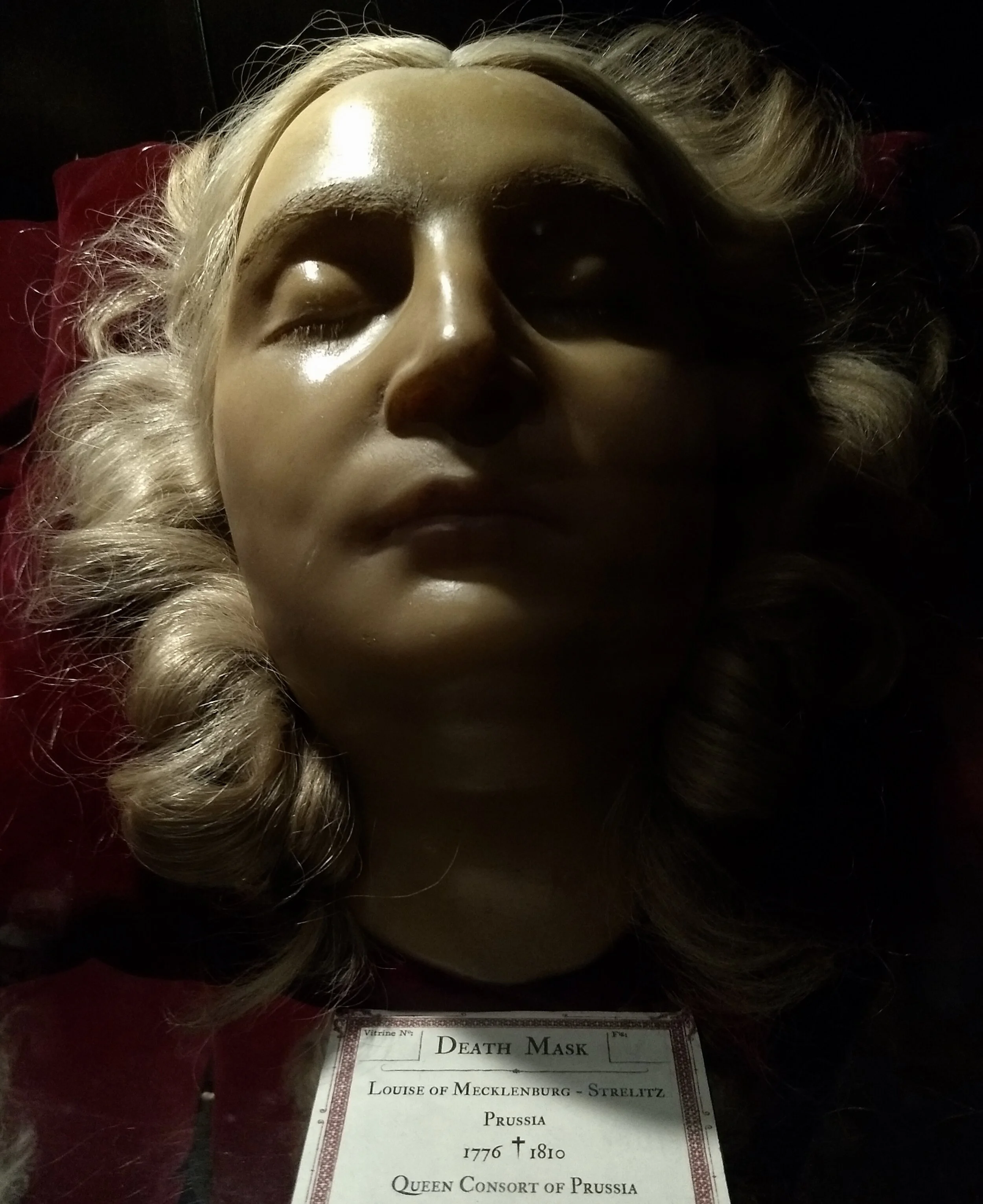

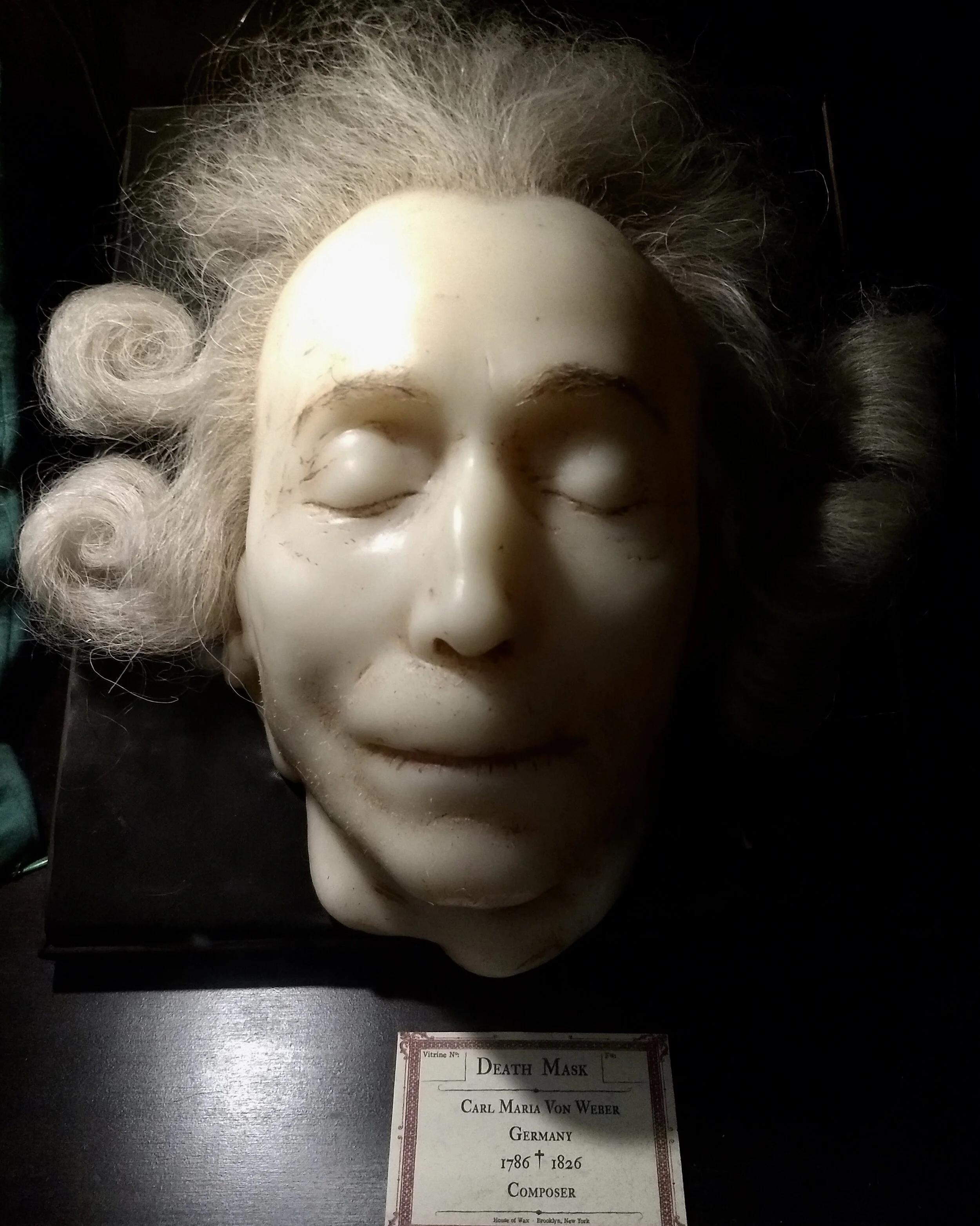

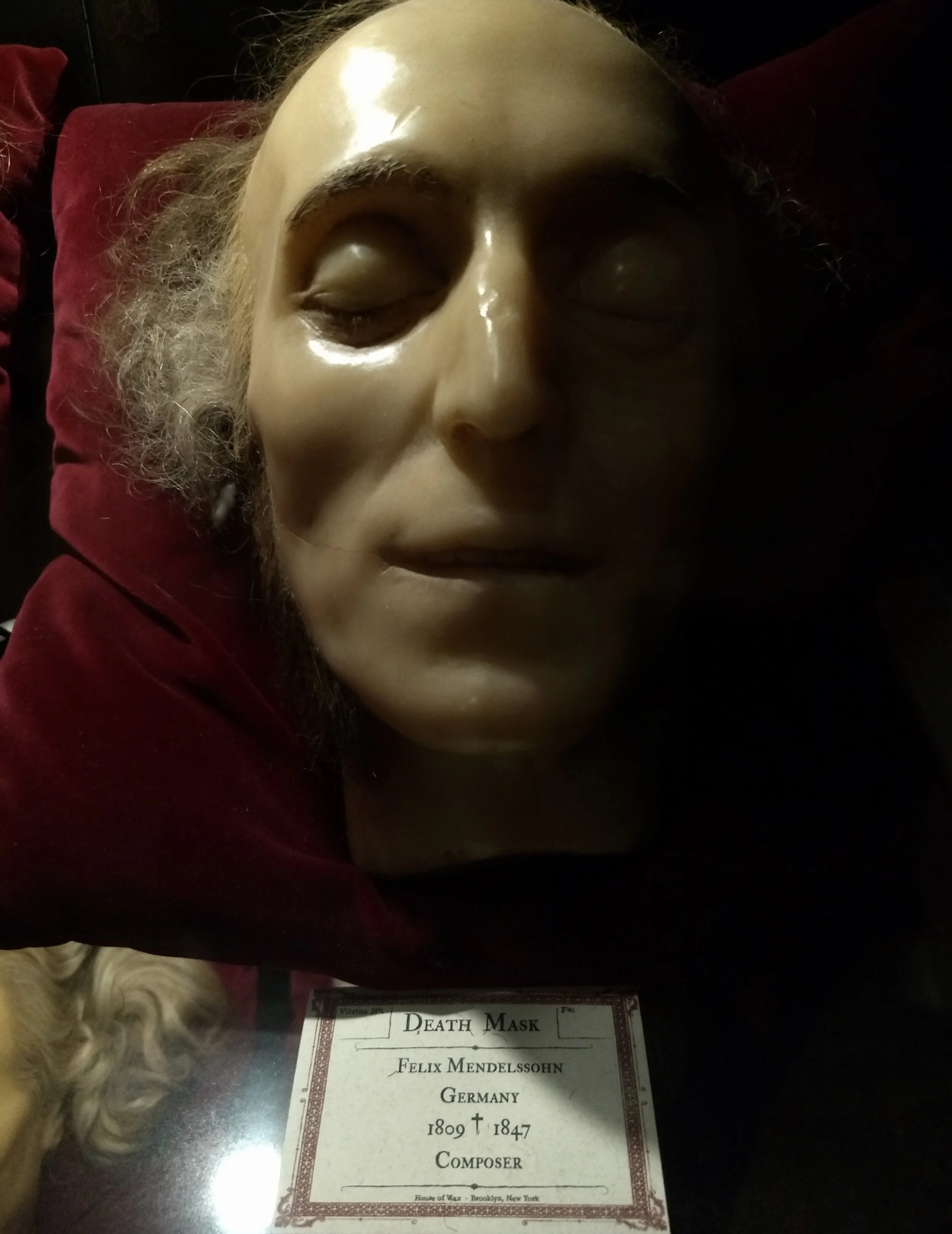

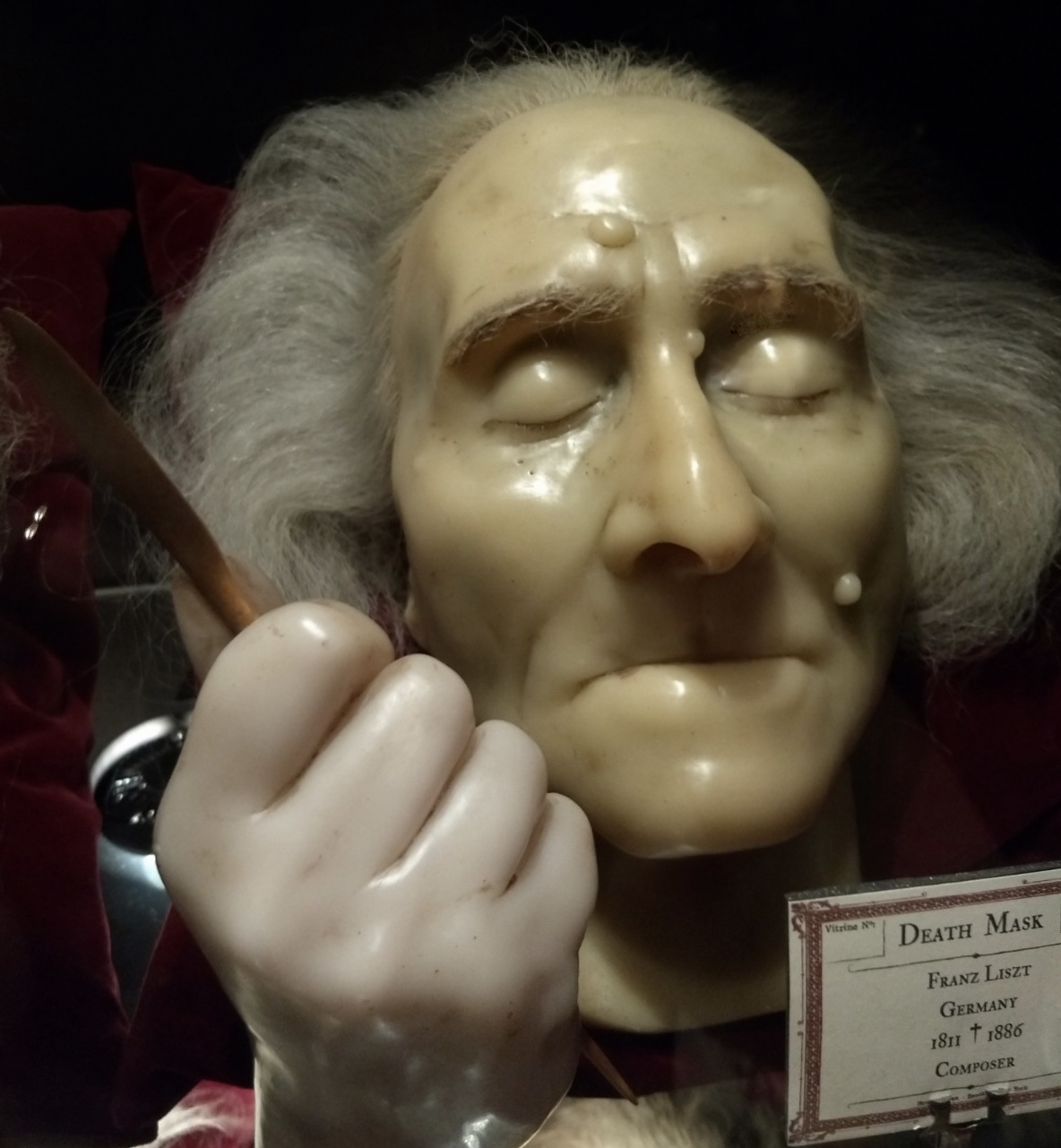

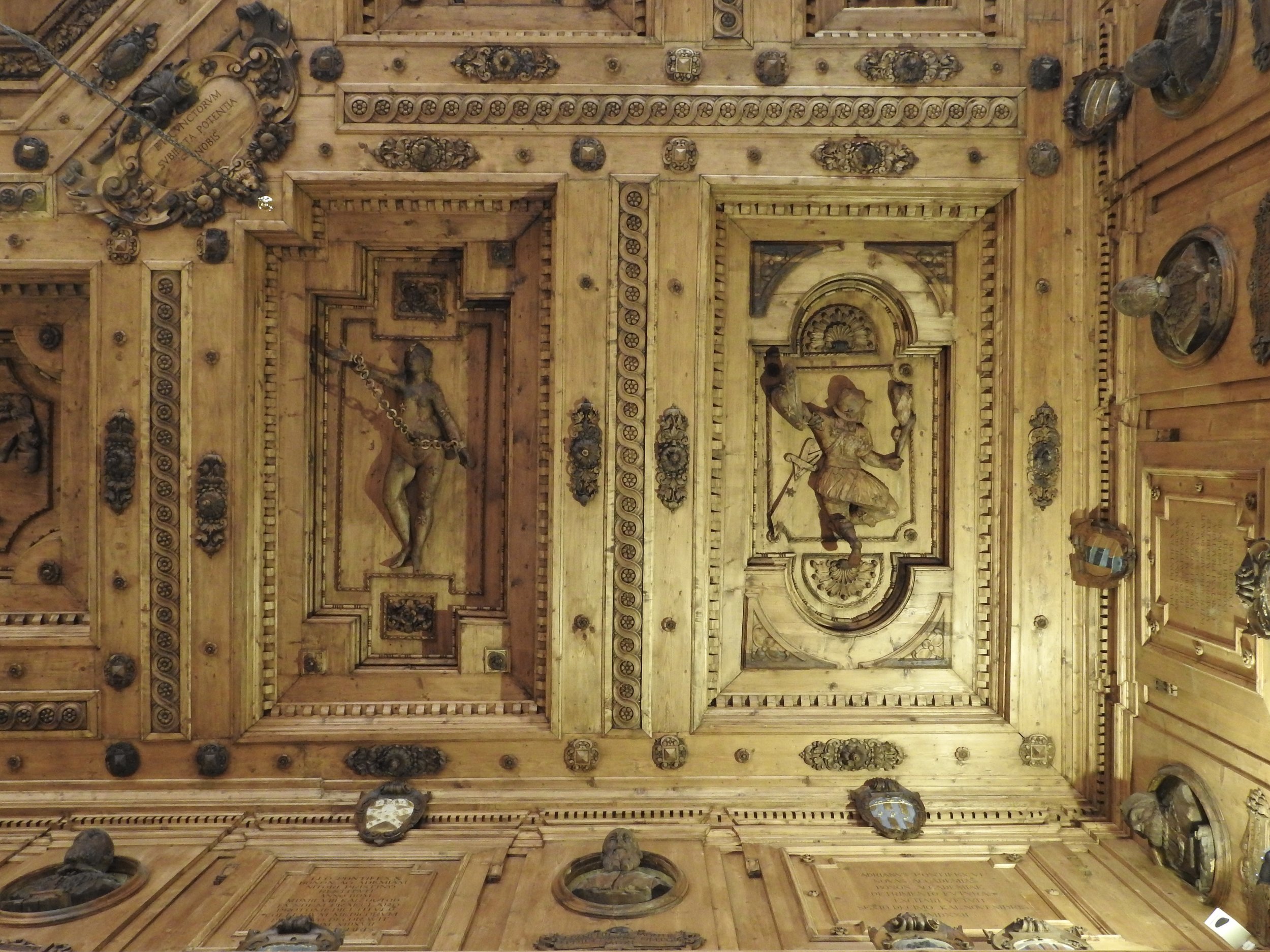

To enter the surreal bar, visitors must pass through a short, narrow passage bordered on either side by anatomical waxes and hyper-realistic death masks.

The collection of death masks represents an eclectic array of personages, from kings to poets, who would have loomed large in the minds of their original 19th century German audience. For contemporary viewers, these masks offer a rare opportunity to see major historical figures much as they would have appeared in life, quite literally warts and all. Standing in front of them, I realized not only how huge Oliver Cromwell (not pictured) actually was, but how much Napoleon resembled Christopher Reeve (on my Instagram feed).

The death masks are also the least squirm-inducing of the entire collection, as most of the faces appear to be asleep; some are even faintly smiling. Deeper within the bar, the anatomical figures become more gruesome, the ethnographic busts more cringe-worthy. There is even an anatomical Venus in the back whose case doubles as a particularly boxy table. The walls around her are filled with odd juxtapositions of disembodied male hands pulling infants out of partial female bodies, half-figures showing the effects of extreme corsetry, fully clothed men, and more ethnographic busts.

Per usual, the images I’ve included here represent the photos I think came out well enough to post. There were several interesting examples I either couldn’t photograph due to their contextual conditions or whose photos were too blurred/marred by weird reflections for public consumption, including those of Cromwell, Henrik Ibsen, Kaiser Wilhelm, and Mary, Queen of Scots. If you’re interested in either European history or waxworks, I highly recommend going to check out the full collection for yourself. And, if your stomach can take it, maybe get an anatomical-themed cocktail while you’re there.

To visit: Take the 2 or 3 to Hoyt Street or the BQR to DeKalb, then walk to 445 Albee Square W (look for Target sign). Once inside the mall, follow the escalators up to Alamo Drafthouse on the fourth floor and cross its Shining-inspired carpet to the House of Wax sign that shines brightly above the otherwise dim bar. Entrance is free.

Further reading:

“Castan’s Panopticon, Berlin,” In the Jungle of Cities: https://inthejungleofcities.com/2017/11/06/castans-panopticon-berlin/

“House of Wax,” Atlas Obscura: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/house-of-wax

Lauren Oyler, “Death in the House of Wax,” Vice: https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/nz8pjw/death-in-the-house-of-wax

Noémie Jennifer, “19th Century Wax Figures Slice Open the Human Body,” Vice: https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/78e73z/19th-century-wax-figures-slice-open-the-human-body

Ryan Matthew Cohn, “Museum,” House of Wax website: http://thehouseofwax.com/#museum