Symbolic animals—particularly those representing religious figures, places, powerful families, or moral qualities—are common decorative motifs in medieval and Renaissance art and architecture throughout Italy. Unicorns, however, remain rare in even this extensive bestiary. So when they kept popping up in Ferrara, I (and the 12 year old still inside me) took note.

The Estes, who held power in the region from the 13th to 16th centuries, seem to have adopted the unicorn—particularly the unicorn with its horn pointed downward in a pose of purification—as one of their family symbols to highlight both their land reclamation projects (occurring primarily in the 14th–16th centuries) and their ability to bring peace and prosperity to the region. The sumptuous Renaissance Bible of Borso d’Este (1455–61), for instance, includes images of a unicorn using its horn to purify water. Borso commissioned the book a few years after succeeding his half-brother as Duke of Modena, probably as a particularly beautiful piece of propaganda to secure and expand his political role. Significantly, he brought the bible with him to Rome in 1471, where Pope Paul II bestowed upon him the additional title of Duke of Ferrara.

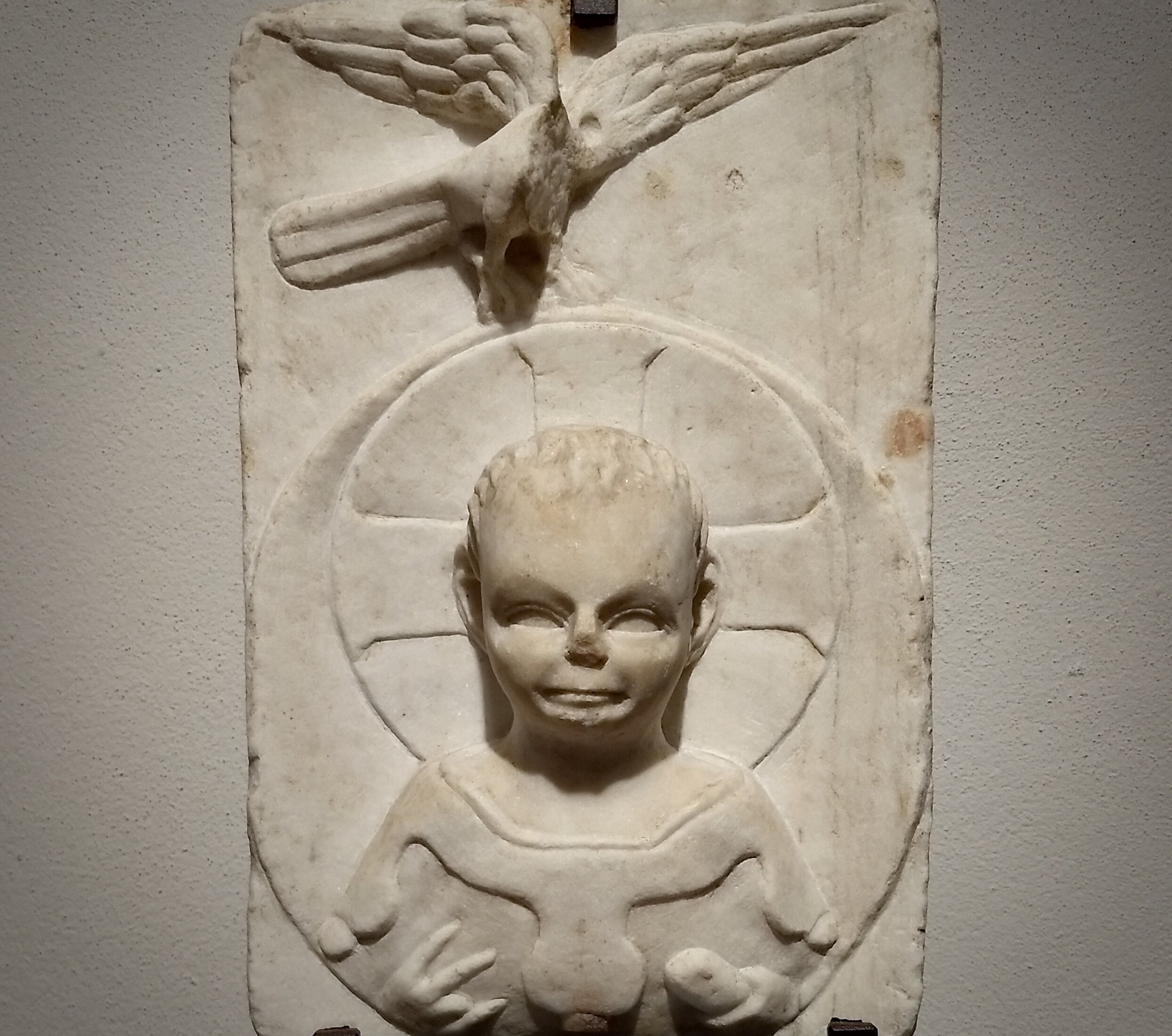

However, at least one of the examples we came across (see 8th century relief, below) pre-dates the Este family’s rise to power in the region. This suggests the Estes didn’t bring the image of the unicorn with them so much as grafted their familial mythology onto a symbol that was already established and well-understood in the region. In so doing, they both increased the prevalence of unicorn imagery in their home city and co-opted the unicorn’s attributes as their own.