Villa Barbaro, also called Villa di Maser, is one of the most famous villas in Italy, known both as a fine example of Andrea Palladio’s (1508–80) domestic architecture and for its extensive interior frescoes by Paolo Veronese.

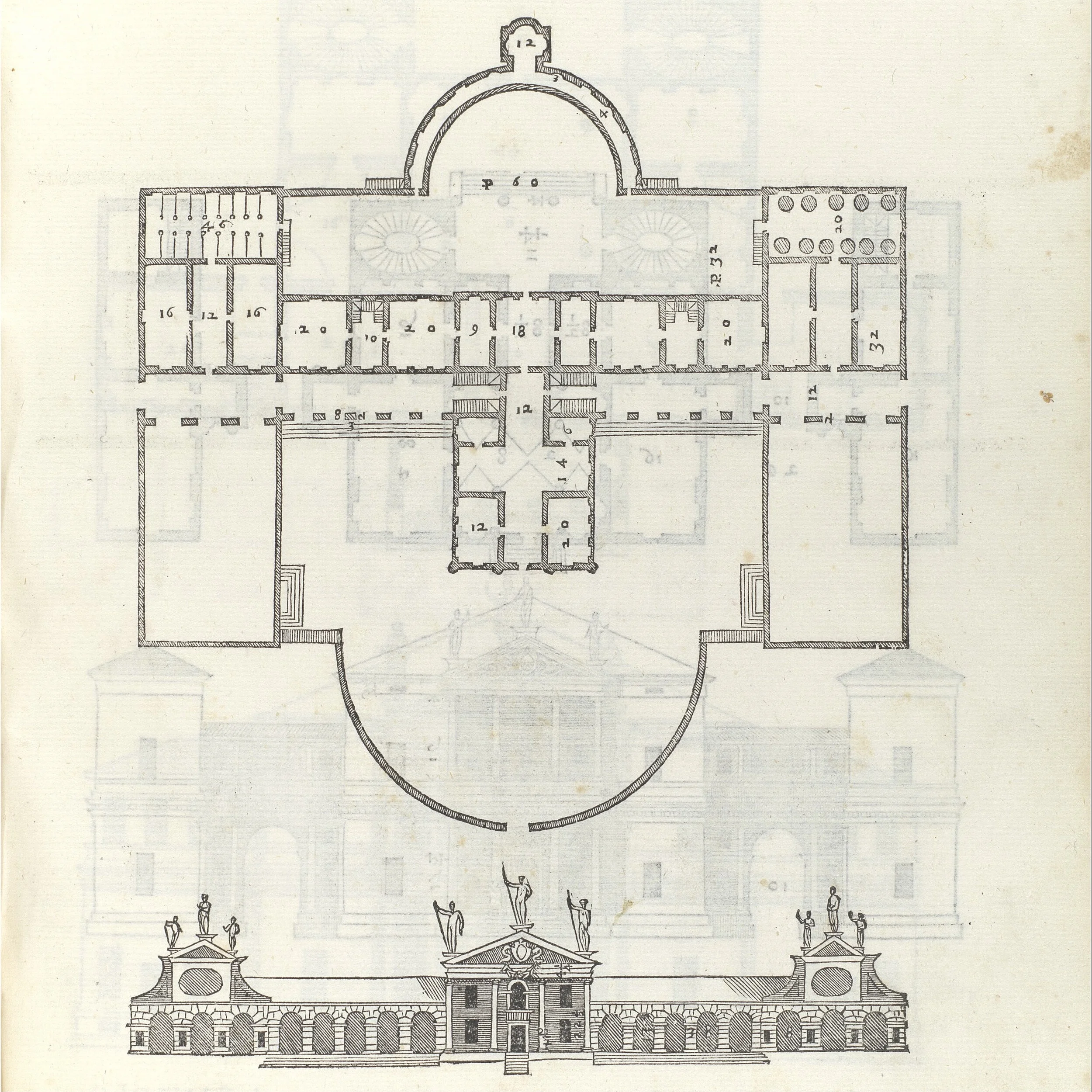

In Palladio’s symmetrical, classically-inspired design, two barchesse (aka, colonnaded storage or work areas) flank either end of the villa, and are connected to the main house by single-story arcades. The sprawling front of the buildings is punctuated regularly with sculptural decoration, additions that add texture and interest to the façade while, from close up, gently disrupting its near-perfect symmetry.

As is typical of wealthy homes from the late Renaissance, the decoration mostly presents a mixture of classical, Christian, astrological, and heraldic subjects. Such a combination not only pays homage to these sources, but visually and conceptually integrates the building’s owners into the intellectual, historical, religious, and political fabric of their period. The fact that the largest, highest, and most central of these sculptures consist of the Barbaro family’s heraldry likewise both announces the family’s ownership of the estate and asserts their importance in society.

What is less typical is the likelihood that much of this sculptural decor was made by one of Palladio’s patrons, Marcantonio Barbaro (1518–95). Carolyn Kolb (and the docent we spoke with onsite) credits Marcantonio—who, with his older brother Daniele (1514–70), commissioned the villa’s construction—with the niche sculptures on the front of the barchesse and in the nymphaeum (30).

Tympanum

Barchesse and arcades

nymphaeum

Located directly behind the main house, Villa Barbaro’s nymphaeum was probably designed by Marcantonio Barbaro and Palladio. Its stucco decoration continues the classical allusions of Palladio’s architecture and Veronese’s interior frescoes, with most of the figures identifiable through their symbolic attributes (see captions). Marcantonio, an amateur artist better known to history and contemporaries as a Venetian diplomat and senator, likely sculpted its four giants as well as the niche sculptures. The reflecting pool doubled as a fishpond and was connected to a natural spring and the villa’s kitchen through a complex hydraulic system. The same system also irrigated the villa’s gardens (Kolb 17).